The April Odyssey and the November Boat

The 1970 event from the Russian perspective

See also: The Odyssey of the Lost Apollo CM

In September 1970, twenty-one weeks after the launch of Apollo 13, the Soviets officially handed back an Apollo capsule to the Commander of the United States Coast Guard Cutter, Southwind. Appropriately enough for this Cold War event, the ice-breaker was visiting Murmansk on ‘a goodwill visit’.

Many commentaries on the lost Apollo command module (CM) have been written from the US or European perspective while the Russian viewpoint has rarely been heard until recently. Russian researcher Andrei Bulatov and naval historian Alexander Boyko featured this event in an article/blog first published on the Russian online forum in 2012 that deals with several aspects of the Soviet-American space program. They have drawn parallels with this Apollo 13 CM incident to earlier activities of the Russian Navy in the Atlantic Ocean (including the events surrounding the loss of the USS Scorpion and the unmanned Apollo 6 test).1 Bulatov and Boyko have reached their conclusions from the facts uncovered during their research. Their unique access to Russian speakers and a fresh perspective on the events leading up to the ‘Murmansk handshake’, led them to postulate that:

The following is their account.

An alternative view of the race to the Moon

Proton launch. |

A paper published in October 2013 by Alexander Onoprienko Illusory Apollo: the Ultimate Mega Show concluded that when compared with the American Apollo program the Soviet Moon program looked "far more orderly and logical, without any plot discontinuities". Onoprienko’s observation as to the state of the Soviet space program in the 1960-70s is evident – relative to the unmanned component of the Soviet space project. But in our view, when it comes to the manned components of the Soviet space program matters are far less straightforward.

By 1970, the USSR had the technology to achieve a manned lunar flyby, but it never happened. Soviet specialists even mastered the most problematic part of the flyby program – skip re-entry – not even achieved by NASA to date. Indeed, the Proton rocket, the Soyuz spacecraft, Blok DM (Blok DM-03), etc., are still in operation today.

Detractors say that after losing the race to the Moon, attempting a manned flyby didn't make sense anymore. Others speculate that it was due to a Soviet-American 'Moon deal'. Neither viewpoint is particularly persuasive to these authors.

The so-called Moon deal hadn’t stopped the Soviet leadership from obtaining their own lunar soil or successfully launching and managing two Lunokhods on the Moon. Yet it supposedly stopped them from undertaking a manned flyby? This would have been the greatest achievement, a technical 'first' which would have remained on the historical record forever, in stark contrast to the sham-ful Apollo saga, which is falling apart before our eyes.

As for the argument that a 'flyby didn't make sense post Apollo', if a project like this was announced now, imagine the publicity and the worldwide attention such a mission would give to present-day Russia. It would be the second greatest achievement after the alleged accomplishments of Apollo. Moreover, these days, there are many who would pay for such a trip, so it could also be a commercial venture. Notoriety, money, and technology are already in Russia’s hands. Yet such an opportunity was passed over in the 1960s and is still being missed today. Why is that?

We know the date that the US Moon program started, but less well known is the date when the Russian program first launched. It was on August 3, 1964, the day when the corresponding Soviet Government Decree was issued, and more than three years after the commencement of the US Apollo program. Of course the development of the N1 rocket was already under way and the Soyuz craft was being developed, but they weren’t originally destined for the Moon. They were intended for other purposes. They only became a part of the Soviet Moon program after the 1964 Decree.

N1 first stage 30 NK-15 engines. |

The original N1 rocket design lacked payload capability to be able to go to the Moon, so about 20 tons were added (with the subsequent redesign). As for the most difficult part of the program – the lunar lander, its design work didn't even commence until the date of the request for proposal (RFP) for the Soviet lunar lander – February 1965. Just four years before the well-known and widely-publicised US Moon landing.

But why was there such a delay? Why did they even take part in a race to the Moon if they had no chance of success? Could Soviet specialists have caught up in just four years? What were the odds of winning the Moon race with such a handicap?

In the opinion of these authors, it was zero.

Joint Venture?

As we know, on September 20, 1963 President Kennedy (speaking at the 18th General Assembly of the United Nations) invited Premier Khrushchev to participate in a joint mission to the Moon. Strange, when just two years previously Kennedy was confident that the US could "win the battle that is now going on around the world between freedom and tyranny.” So what had happened? Did the ‘Evil Empire’ (as Reagan would later call the Soviet Union) turn into an Empire of Goodness in just two years?2

Or did something else happen?

In 1961 John F. Kennedy was an inexperienced White House newcomer and it appears that his advisors let him down at least twice at the very outset of this presidency: a) with The Bay of Pigs invasion, and b) with the public announcement of NASA’s Moon program. By the second year he must have realized that his lunar program was going nowhere and would be looking for a solution. Kennedy knew that NASA was already talking to the Soviets via the Soviet Academy of Sciences, hence this move which was a surprise to some, and very unwelcome to others. However, the problem would soon be 'resolved' for this President and the new administration would have different ideas.

It is the authors’ view that Khrushchev never believed that the US actually had the ability to get humans to the Moon and he wasn’t going to help Kennedy out, probably punishing him for the Cuban insult. But the new US administration came with a problem for the Soviet leadership. While Kennedy had been committed to his manned Moon program, Lyndon B. Johnson (and subsequent US presidents) may not have been so sure of success. On the one hand, if the Soviets were not planning for a manned Moon shot, the Americans could slow down their own program, or even consider shutting it down altogether. After all, if the Soviets couldn’t do it, neither could the Americans. Democrat Kennedy was wrong, it couldn’t be done, period. On the other hand, if the Soviets were indeed close to accomplishing even an unmanned Moon flyby, that would change everything."We can’t do it, but those Soviets can" and that would be a political catastrophe for the US!

In the USSR, the precursor to a manned lunar flyby was the Soviet unmanned Zond flyby program – there is no doubt that the Proton booster and the Soyuz spacecraft were both at a high level of readiness and everything was real: NASA could track these spacecraft all the way to the Moon and back. Indeed, when the first spacecraft to circle the Moon and return its biological cargo safely to Earth – Zond 5 – splashed down into the Indian Ocean the US Navy ships were so close that the Soviet Navy had to guard their capsule from the scouting Americans. At that time not one single Apollo spacecraft had got anywhere near the Moon.

And it was already September 1968!

In The Space Shuttle Decision, T.A. Heppenheimer writes:

In September, the Soviet Union carried out an important lunar mission, Zond 5. This spacecraft looped around the Moon, returned to Earth, reentered the atmosphere, came down in the Indian Ocean, and was recovered. Two turtles were aboard, and they came back safely. An impressed Webb described this flight as "the most important demonstration of total space capacity up to now by any nation".

... Zond 5 raised the stakes. All along the goal of Apollo had been to beat Moscow to the Moon; yet by sending a cosmonaut in place of the turtles, the Soviets could still win the race with another Zond mission. While Zond would only loop around and not land on the Moon, if cosmonauts were to do this, they would become the first pilots to fly to the Moon. Subsequent Apollo landings then would appear merely as following in Soviet footsteps.

Our hypothesis is that the Soviet Zond program scared the living daylights out of the Americans and thus forced them into faking the December 1968 Apollo 8 flyby. During the Zond program, the true masterpiece of space manoeuvring, the skip re-entry, was also accomplished, but it was not achieved without great difficulties. In fact both sides had too many problems to overcome when it came to safe human spaceflight. Not least that of effective shielding from radiation, still not resolved to this day.3 And note that skip re-entry, now esteemed an essential requirement for returning manned lunar spacecraft, has never yet been performed by any US spacecraft large enough to carry astronauts.

As a result, we consider that the Soviet manned Moon program was never intended to actually send men to the Moon but was instead planned to push the US and NASA into faking their own Moon missions. The US actions could then be used to the political and economic advantage of the USSR – if proof of such fakery was obtainable. By the time that Apollo 8, 10, 11 and 12 were programmed, half of this plan had already been achieved. The second half, obtaining leverage by producing outright evidence of the fakery, might be a longer game, monitoring Apollo launches and splashdowns while waiting for the inevitable – the moment when something went really, really wrong.

The Real Odyssey

Yet when the most obvious proof of fakery was openly presented to the world more than 45 years ago it was generally ignored.

Apollo CM handover in the port of Murmansk, Russia.

The Gift of Fate

In one version covering the Apollo CM captured by the Soviets, the author Mark Wade is obviously trying to play down the event, but one thing is quite clear. He writes, “The story remained obscure and unknown for 32 years until a Hungarian space archivist came across a picture of the event in his archives...”

Such a statement is entirely untrue, and in our view, it’s totally inexcusable for an expert to make such a statement. In 1970 nearly every local newspaper in the US reported on the event – not least because the Soviet Union made it impossible to keep this matter silent. So it didn’t take long to learn more about this story in detail by checking old news reports. According to the official story, it was a Soviet fishing vessel which accidentally found a very important artefact of the US space program in the ocean. Actually Mark Wade thinks the vessel could have been a spy trawler, but in this case why such secrecy about which both parties have kept quiet (and have continued to do so) for over 45 years? No reference was made to any such fishing boat in the US newspaper articles published in the 1970s. The blog livejournal features many of these, in Russian and in English, and one of the longer articles came from the US military magazine Stars and Stripes (Vol.29, No.141):

Russia Says Apollo Capsule is Found, will be Returned

Sunday September 6, 1970

MOSCOW (UPI) – The Soviets have plucked from the ocean a U.S. space capsule they describe as part of the Apollo Moonshot program and plan to return it to American officials this weekend, the official TASS news agency said.

Checks with U.S. Embassy officials indicated the Soviets have had at least two weeks to examine the space hardware and U.S. officials knew it, but their decision to return it at this time came as a surprise.

One embassy spokesman said U.S. officials had viewed the object Friday [September 4] and could not confirm it was an Apollo program item. But he added, “it was my impression from their report it is a whole piece of equipment” and not a fragment.

The Soviets said bluntly they intended to put the capsule aboard the U.S. icebreaker Southwind, which was putting into the port of Murmansk Saturday for three days. U.S. officials said subsequently they had asked Washington for permission to make the transfer.

A three-paragraph announcement by TASS Friday afternoon gave the first inkling the Russians had any U.S. space gear.

An “experimental space capsule which was launched under the Apollo program and was found in the Bay of Biscay by Soviet fishermen will be transferred to U.S. representatives,” it said.

“The U.S. icebreaker Southwind will come to Murmansk to take the capsule on Saturday [September 5].”

Prior to the TASS announcement, the US embassy had announced the Southwind would stop at Murmansk from Saturday through Monday [September 5-7] to afford its crew “rest and relaxation.” It described goodwill aspects of the visit and nothing more.

When queried on the TASS report an embassy spokesman said the Soviets had taken the decision without notifying U.S. officials.

“The Southwind is going to Murmansk for the reasons stated, rest and relaxation, and I think it’s a pretty good guess the commanding officer of the ship doesn’t know anything about this,” he said.

‘Fallen From Space’

“The Soviets did tell us about two weeks ago they had something of ours that had fallen from space and that it was in Murmansk, but they apparently decided without telling us to take the occasion of the Southwind visit to give the hardware back.”

Another embassy spokesman added later that U.S. officials who had gone to Murmansk to greet the Southwind had seen the space equipment and taken serial numbers, which had been wired to Washington for identification.

“We have told Washington,” he said, “that we would like to put it on this ship, which is calling at Murmansk on other business, if it is what it appears to be and if the commanding officer approves.”4

Loading the CM aboard icebreaker Southwind at Murmansk, Russia on the weekend of September 5-6 1970.

The TASS news agency put out this news on teletype, and as a result UPI reported the event worldwide. The USSR openly stated that the “experimental US space capsule was launched as part of the Apollo program.”

What is interesting is that TASS only published this news abroad. It was never mentioned anywhere in the Soviet press. So it was intended for Western readers only. Yet, Mark Wade infers that he knew nothing about it and that nobody else knew. Nor did he make any attempt to find out. He writes: “The truth only emerged 32 years later – the Soviets recovered an Apollo space capsule in 1970...”

In fact in 1970 anyone in the United States could easily have read about it. And on September 15, just ten days after the Murmansk handover, the NASA Administrator, Thomas O. Paine left office – a mere coincidence? Probably not.

USCGC Southwind crew with the Apollo CM (in the background) returning from Murmansk.

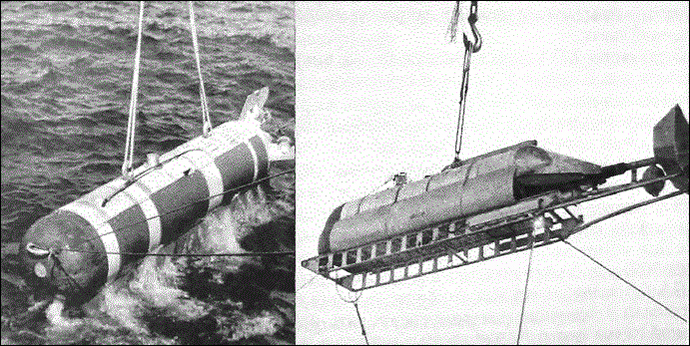

Finders Keepers – the Apollo 13 CM and the Soviet submarine K-8

There is another candidate for the finder of this module, and it's not a fishing vessel but a Soviet nuclear submarine Project 627A, K-8, designated as the November class by NATO. There is a rather brief Wikipedia article about the sunken Russian K-8 November class submarine of the Northern Fleet. Russian researcher and rocket scientist Arkadiy Veljurov was the first to suggest a connection between the captured Apollo CM and the ill-fated Russian submarine K-8 of the Northern Fleet that is said to have sunk in the Bay of Biscay on April 12, 1970.

Some time ago we asked Veljurov, “Was it just a wild guess or was there something behind your speculation?”

He replied, “Would you believe it if I said that I knew someone who was actually escorting this Apollo CM?” But he was not suggesting that the loss of the Soviet submarine was intentional. His personal opinion was that the K-8's unlucky accident might have helped in distracting the Americans who were looking for their Apollo 13 CM, giving the Soviet Navy the opportunity to capture it.

Another Apollo investigator Dr. Alexander Popov went farther and proposed that K-8 was used as bait to distract the Americans, thus helping the Soviet Navy capture the Apollo 13 CM that would be produced in Murmansk just over five months later. But Popov didn’t have much by way of supporting evidence, just his own reasoning, which may or may not be correct.

K-8 November class submarine

Enter the Visitor

This remained the state of affairs for some time until someone with real nautical experience came along. Alexander Boyko. Known online as Visitor, he has sourced the remainder of the investigation into this incident.

His story could make Tom Clancy and John le Carré rather envious.

As part of Visitor’s investigation, he decided to check out the official K-8 story. There is a considerable amount of material from Russian sources concerning this submarine. According to the storyline, after urgently surfacing, the K-8 was visited by two ships: a Canadian dry cargo ship and a Bulgarian steamer. Both allegedly came along purely by chance.

We found sixteen accounts from K-8 crew members concerning the encounter with the Canadian vessel. Since the differences between the sixteen descriptions of this event are relevant, the fine detail is to be found in the Appendix. This is brief overall summary of that encounter:

That day at 14 hours 15 mins we saw a ship on the horizon. The commander ordered us to fire five red flares. The ship changed its course and headed in our direction. When she came closer, we saw a large maple leaf on the funnel and the inscription "Montreal" on the side. The name of the ship was Glow de Or (or Clyv de ore, or similar). She was a Canadian cargo ship. At a distance of 100-150 metres (or 15 cables) she went around our boat and resumed her previous course. We didn’t ask for help. The Canadian captain might have been scared by the machine gunners(!) on our deck. Having seen that it was the 'capitalists', not to mention a NATO country, our commander decided not to make contact. Seemingly, the Canadians reported our presence and shortly after the US spy plane "Orion" appeared and began dropping sonar buoys.

Although the official storyline states that the K-8 already had a fire on board, and 30 corpses, here we see that apparently they were in "no need of assistance”, and to emphasise the point there was a squad of sailors with machine guns led by their commander. This way they successfully repelled aid, and disgraced the unsuspecting Canadian crew for not providing help while doing so. Such is the official story.

Given the wildly varied and often inaccurate descriptions of this encounter it’s useful to note that as a general rule the ensign flag denoting the nationality of the ship is not hoisted on the stern until 8am. For identification purposes, the funnel markings state the ship’s owner; the home port is only inscribed on the stern of the ship; the name of the ship itself features both on the stern and on the two bow sides.

So it’s also significant as to what's missing from the K-8 witness descriptions. For example, none of these witnesses reported such facts as the course of the vessel, (whether she came from the north, south, etc.) nor where she was going to when she left. Was she loaded or had she dead weight? How was she painted, what was her superstructure, her flag?). It appears that these details were so insignificant that no one had one noticed them.

Instead, these eyewitnesses and subsequent authors have all reported what they could not possibly have seen. It is a fact that they cannot have seen the ship's name as described because neither the English nor the French language (used in Canada) have words such as "clyv" or "clyvde." While this could have been an honest mistake, perhaps a typist’s error, it occurs across too many of these descriptions for that to be the case. Most likely it was deliberately distorted. There are several possible reasons for this, firstly, using an inaccurate name avoided the possibility of any legal claims from the ship owner, should (false) reports of not providing help for those in peril at sea later emerge.

However, the fact is, at that time there was such a vessel with a similar name, and she could have encountered K-8 during April 1970.

We are talking about the Clyde Ore.

The Clyde Ore arriving off Eston Jetty, River Tees, c.August 1965. Navios insignia on funnel and on prow, ship’s name on side.

Originally constructed as a deep-sea ore carrier, this vessel was one of eight sister ships built in 1959/60 by Schlieker-Werft, Hamburg, West Germany specifically for a long-term charter arrangement with Navios Corp. of the Bahamas and destined for the iron ore trade between Venezuela and Europe relative to the U.S. Steel interests.

The ship’s owner was the Navios Corp this insignia was painted on the funnel. Clearly, it does not look like a maple leaf. |

Of these eight ore carriers, four were owned by the German company Transatlantic Bulk Carriers and registered out of the port of Monrovia, Liberia. Named after German rivers these were the Ems Ore, Rhine Ore, Ruhr Ore and Weser Ore. The other four were named after British rivers – the Clyde Ore, Thames Ore, Tyne Ore and Tees Ore – but owned by the American Polaris Shipping Company.5 One source states that the flag of these ‘British River’ ore carriers is not specified, but then other sources state it carried the Liberian Ensign. This is confirmed by the Clyde Ore’s home port inscription, painted smaller than the name Clyde Ore it was – MONROVIA.

Liberian Ensign |

The Liberian Ensign is very similar to the US flag but it has just one large star in its upper left corner. Certainly Comrade Commanders and sailors couldn’t possibly forget such basic things as how to determine the nationality of a ship (it is determined solely by ensign). How the K-8 officers managed to see a maple leaf on the funnel and how they missed the ensign at the stern is utterly inexplicable – so much so that it is nonsense. Although it is true to say that such confusion renders the tale so unbelievable as to incite most people to simply walk away. And that is a good disinformation tactic.

Example of a Liberian registered ship with the home port of Monrovia and the Liberian ensign flying on the stern

Frankly, the thinking that this was a Canadian ship out of Montreal seems like a story concocted by landlubbers and then distorted (wittingly or otherwise) through verbal transmissions across several sources. Everyone saw MONROVIA? So now it’s Montreal, and Montreal means Canada, and Canada means NATO, and NATO means we don’t surrender our submarine! This is another distortion that supports the aforementioned avoidance of legal claims, since it too provides a political (but entirely invalid) reason for the universally acknowledged code of help to those in distress at sea to be conveniently brushed aside.

Why would that be necessary?

Conclusion to this first encounter

Contrary to Veljurov’s thought that K-8 ‘accident’ helped to distract the US from their mission of monitoring the seas under the Apollo 13 launch area we propose another scenario. The K-8 on a covert mission to extract the Apollo 13 capsule from under the noses of the US, should it fail, was very near to the area southwest of the Azores where it was likely to come down should there be a malfunction soon after launch.

This K-8, while possibly using the pretext of an ‘accident’ on board the nuclear boat to allay the suspicions of any observers or passers-by of the wrong sort, was acting as a location marker for the 'wolf pack' of additional Soviet ships required for this covert operation.

So the officers of the K-8 were indeed expecting to rendezvous with another ship but the Clyde Ore was an unexpected visitor and the improvised scenario of flares and then "stand-off we do not require assistance from you" was fully intended to send them away. It also enforced the notion to observers that the sub was possibly in trouble. This covert mission with all its artifice, was supported wittingly or unwittingly, by a particular set of circumstances.

In April and May 1970 the Soviet Union launched Okean 70, the largest naval exercise ever seen. During April the Soviet fleets proceeded to their positions ready for the May 1 start, and thus by mid April the American and the British navies and air forces were accustomed to the proliferation of Soviet ships in the Atlantic. And just prior to the Apollo 13 launch, these same observers were also being habituated (or perhaps trained) to the very idea of a Soviet sub in trouble in the Atlantic, when on Friday April 10 American Orion aircraft took photos of a K-8 on the surface.

The Komsomolets Litvy and the K-8 Submarine.

The US press later inferred that the sub was possibly in trouble, as it was accompanied by two other Soviet ships, one of which, the Komsomolets Litvy, is seen in this photo. The story was that the sub had lost power. Yet this photo shows the sub is seemingly in good shape, moving forward under its own propulsion. Even though the press stated that it was in the Bay of Biscay, one small section of sea does not provide confirmation of that fact, and all the photos published in the press make it impossible to evaluate the exact location of the sub. Nor do we know who exactly took this picture – is it from the deck of the other Soviet ship or does the angle of the photo infer an overflying US Orion? It is therefore not clear whether the sub in this photo was the ‘covert mission K-8’ or a decoy K-8 located in the Bay of Biscay – or elsewhere.

Sink

Whereas the English language Wikipedia has a rather brief article on the K-8 incident, the French language Wikipedia has a far more in depth coverage6 and its report on the K-8 crew concurs with V.V. Shigin, the Russian author of Biscay Requiem:

There were 125 people on board the submarine. Officers: 28, enlisted servicemen: 31, sailors and petty officers: 66. Fifty one were married. In addition to the regular team, there were ten individuals on board attached from the staff of the division and from other crews. In addition, twelve apprentices were taken.

The loss of a submarine in the Soviet Union was generally punished by court-martial. For example, both commanding officers of the K-19 submarine were severely reprimanded for a collision with submarine USS Gato on November 15, 1969, even though the K-19 didn’t actually sink, and there were no casualties on board. Yet the crew of this November boat, apparently suffering from a fire on board and eventually sinking were rewarded for their efforts. 122 awards were assigned to the crew with the Commanding Officer V.B. Bessonov becoming a Hero of the Soviet Union, the highest distinction in the Soviet Union.

All that being said, the photos and the storyline of an implied accident and subsequent sinking of a K-8 somewhere in the Atlantic certainly prepared the way for the subsequent disappearance of the covert mission’s special K-8.

That is, after it had encountered that second ship.

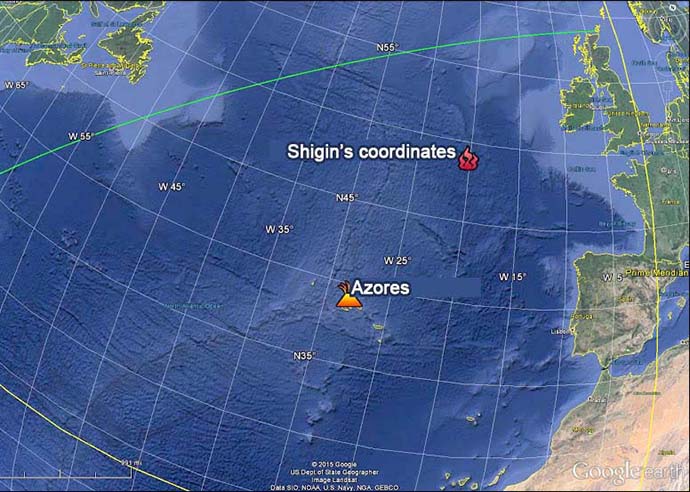

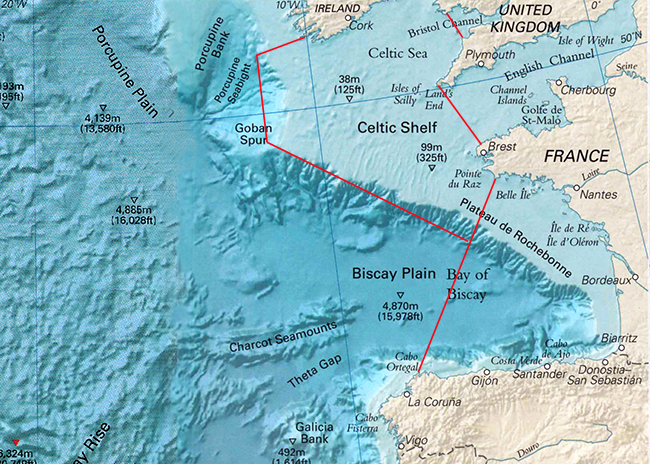

Northern Atlantic. “Shigin’s coordinates”: 48° 10'N, 20° 06'W –

green line is the shortest route to Cuba navigating around the north of the British Isles.

The Second Encounter with the Bulgarian cargo ship Avior

The following summary of this second encounter is drawn from another set of 16 accounts provided by those same K-8 witnesses:

On the horizon above the stern we saw the outline of a ship. As she approached, we saw a superstructure and a funnel, but no markings regarding her nationality. The funnel was not white, but cream [or yellow] with a red stripe and without a hammer and sickle. Then we saw the name Avior and only when she caught up with us, using a megaphone (made from old tin cans of crackers) did we make contact with the bridge. As it turned out she was a Bulgarian cargo ship, and the captain-coach was our compatriot. The home port was Varna and they were going from Hamburg to Cuba. Our radio did not work, and only thanks to this cargo ship, in the second half of the day, were we able to send a message to Moscow about the accident through the Bulgarian port of Varna.

Many of the accounts of this second encounter [Appendix C] contain impossibilities: there is the same odd use of five red flares (a five-red SOS flare or similar signal is not used in navigation) and remembering that the funnel does not designate the nationality of a cargo ship we find similar problems with the descriptions of vessel identification,

“The question arises: whose vessel was this? Then we saw the name Avior…On the yellow funnel a wide red stripe stood out. It seems ours!”... “Identify your nationality! Kashirsky shouted through the makeshift megaphone made from a biscuit tin.”

Example of a Bulgarian funnel.

Here it’s useful to note that by April 1970 V.A.Kashirsky was deputy commander of the 17th submarine division of the Northern fleet (earlier, in 1968 he was considered the best Northern Fleet CO in intelligence tasks, taking part in the famous 1969 Caribbean Navy exercise (the Second Caribbean crisis). He also appears to have been excellent at being in two places at the same time: his biography states that from 1965 through to November 1970 he was CO on a K-21 sub. Yet here he is in April 1970 shouting from the sail of the K-8. It’s most likely V.A.Kashirsky was indeed the field commander of the covert operation “How to steal a NASA capsule and get away with it.” But quite how he managed to be on K-21 and K-8 at the same time is a mystery.

Is all this description of the encounter another mystery story created by landlubbers? Or a sign of more guesswork? The colour of the funnel was described as cream in one description, gold in another, yet the photos of the Avior show a funnel with a bright yellow background to the red stripe. These funnel markings belonging to the Bulgarian Shipping Company were entirely sufficient to identify the ship as ‘one of theirs!’ That is, a part of the USSR.

Yet, for some obscure notion, and there had to be a reason for their initial reticence, when it came to truly ascertaining the nationality of the ship, it was only the name of the home port of Varna on the stern, that finally convinced the K-8 crew that ‘brothers’ had truly arrived. That – and the fact that the Captain turned out to be a Soviet.

The Avior in the port of Vancouver, January 2, 1968.

In stark contrast with the earlier encounter with that so-called 'Canadian' ship, the Clyde Ore where 45 years later witnesses and writers remembered the exact time of 14 hrs 15 mins (possibly related to the fact that Soviet Navy submarines operate on Moscow time GMT+3) nobody can provide a precise time for the encounter with 'our' Bulgarian.

As for the location, the only specific coordinates supplied for this encounter – 48°10'N and 20°06'W – were given by author V.V.Shigin and have been uncontested by any one else. Which is remarkable, given that his account of the K-8 sinking is titled Biscay Requiem, yet his coordinates lie much further west, well beyond the boundary of the Bay of Biscay and even the Biscay plain. Unable to read the full text of this book, which is only available in Russian, such discrepancies incline the English-speaking reader at least, to suspect that disinformation is at play – unless Shigin has been as confused as everybody else about the number of K-8 sinkings in the 1970 in the Atlantic. Of which more later.

Sea boundaries of the Eastern Atlantic.

The Bay of Biscay limits are defined by France and Spain. The Biscay plain lies beyond its boundaries and Shigin’s coordinates lie further to the west of even this plain.

What can be established is that via voice-communication at a distance by means of a "rolled-up biscuit tin can", a "friend or foe" procedure took place. And, more specifically, "the right ship” turned out to be “The one they had been waiting for at the appointed time” as Boyko puts it. If it’s any help, on the morning of April 12, 1970 with reference to GMT/UTC, sunrise at was at 5.42 am, dusk started at 4.30 pm and sunset was at 7.10. Yet, at 4 am those present on the bridge (all commanders – a senior on the boat, CO, chief officer, deputy political commissar and a signalman who joined them) Kashirsky, Bessonov and Anisov were quickly encrypting a wireless message – even before having found out who and what they were meeting. So clearly they were expecting a meeting with a ship – but was it really the Avior that they were expecting? Why were they so unsure they had to look at the stern to assure themselves of the home port?

The Cargo Ship Hadji Dimitar

Svetoslav Yurekchiev |

Actually there was reason to doubt whether or not THE ONE was truly the Avior. The following is from Svetoslav Yurekchiev’s story, then the second engineer on the cargo ship Hadji Dimitar:

I know some cargo mariners who have two military decorations, the Order For Services in BPA (Bulgarian Army) and an honour letter from the Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Navy. They are the members of the crew of the cargo ship Hadji Dimitar. In April 1970, we navigated the swell in the Atlantic, north of the Azores. Almost immediately after the start of my second engineer’s watch "four to eight" (04:00-08:00), despite the fact that the main engine was running on heavy fuel, by telegraph I received the command "Stop."

Since according to the instructions, switching to manoeuvring mode requires changing to the light fuel oil, which takes about an hour, I realized that something extraordinary had happened. I immediately executed "Stop" and after a few minutes the command "Full Astern" followed, and then there were repeated instructions "Ahead–Astern". I sent a man to the bridge to find out what had happened and whether we should switch to light fuel oil. The boatswain came back and vaguely explained that some vessel was giving light signals for help.

At dawn, we saw a nearby Soviet nuclear submarine...

... All this time I had been in the engine room without a break. We carried out hundreds of manoeuvres as part of the [crew rescue] operation. The next day the first Russian ships came down, they took all their people, and seemed to have organized the towing of the damaged boat. We continued to sail on schedule.

He is not alone. This account of that same incident is from the Varna newspaper Narodno Delo (People's Cause), issue 05.01.2010: Bulgarians Rescued the Crew of the Soviet Nuclear Submarine by Zdravko Roev:

40 years ago during April 1970 in the Atlantic Ocean north of the Azores, the crew of our ship Hadji Dimitar rescued the crew of the Soviet nuclear submarine K-8 class Kit (Whale). The operation was carried out in rough seas. [Beaufort scale 6 Ed.] At that time our local Varna resident Dimitar Nenkov was the ship's motor-mechanic. He displayed considerable competence in conducting the rescue operation, and was awarded a Certificate of Merit by the Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Navy, Admiral Gorshkov. Despite 40 years since the tragedy, Dimitar Nenkov remembers details of the rescue operation well:

... "The officer of the watch noticed the submarine in the dark, just by chance. A Russian sailor was giving light SOS signals. Fortunately, the captain on the Bulgarian ship was a Russian, Ram Smirnov. According to the Russians this helped them to get onto a friendly ship...

... “The second engineer, Svetoslav Yurekchiev did everything possible to accurately follow commands from the bridge. For motor-mechanics time was passing very slowly. In the first few hours no one suspected that the boat was nuclear-powered except for the Russian captain...

... When the rescue operation was completed, the second order came from Varna: Hadji Dimitar had to stay near the submarine.”

The second engineer’s story paints an unambiguous picture. According to him, the Bulgarians either intentionally or by accident encountered the boat – to suddenly give the command “Stop” meant they were making an emergency stop and a jammed fuel pump due to a switch to light fuel oil is the best evidence of that. The “Full ahead" “Full Astern, and “ahead-astern” all indicative of manoeuvring activities. And only at dawn would they find out who exactly was shooting five red flares. (Cargo ships reference the time zone they find themselves in taking into account any daylight saving time in operation). And all of these "early in the morning on the horizon" comments we’ll leave to the conscience of those who wrote (or made up) their stories.

The Bulgarian connection and how the Avior was lost

But this is not the most interesting part of this Bulgarian story. It is the name of the ship that’s interesting. On the website of the school which Yurekchiev attended, and where his story is published, there is mutual surprise that all the Russian websites mention the Avior, omitting the real name of this ship, namely the Hadji Dimitar.

It’s next to impossible to believe that Svetoslav Yurekchiev and Dimitar Nenkov could confuse the name of the vessel on which they were working. And it’s next to impossible that the Avior was present at the K-8 location in 1970. So how to explain this anomaly? For that we have to go back to just after the birth of this ship (which was in 1956, in Kiel and when built she was called the Bronnoy. She had a length of 151.4 m, a beam width of 18.9 m, a draft 9.09 m, and was 13,440 tons deadweight. The main engine was diesel MAN 5400 hp. The vessel’s speed was up to 14 knots.

Four years later, and Bulgaria entered the scene. By 1960 it was the first socialist country that achieved considerable success in the field of bankruptcy. No one gave them money, not even Khrushchev. Scratching their heads, the Council of Ministers disregarded the sacred principles of socialist economics and on December 3, 1960 secretly formed a joint venture with one Georgi Naydenov at its head: Texim, was born. On March 11, 1966 Texim purchased the cargo ship Bronnoy and promptly had its name changed to the Avior. The story of the Texim company’s rise and fall is in itself incredibly interesting and relevant to this article, because a seemingly normal Bulgarian cargo ship was in fact, owned by a company run by an intelligence officer of the Bulgarian State Security. [Appendix D]

The Hadji Dimitar – formerly the cargo ship Avior.

Geto

Greed is good: The intelligence officer Georgi Naydenov (nicknamed "Geto") formerly of the Vasil Levski Brigade had exactly the right connections to do business with his equals across the globe. As for international covert operations, he was a past master. By the time Geto had grown from being a young guerrilla to being an important member of the Bulgarian Intelligence Service and in charge of Texim, he had got his hands on all the US funds to be found in the country, all $2,314 US of it. He had collected 10,000 tons of various small arms ("we have plenty of this stuff...") loaded it onto the ship Rodina (Homeland) and sold rifles to the Algerian FLN, cheating the French Intelligence and other Sûreté Générale types while doing so. This action alone earned the state treasury more than $50 million US. And off we go – from 1960 through to 1965 the capital of the state enterprise Texim grew to US $136 million. The Bulgarian Head of State, Todor Zhivkov, stopped walking around the Socialist Camp with a beggar’s hat.

Along with arms exports, Texim was eventually involved with offshore banks, cigarettes, a trans-Atlantic air service, agricultural aviation in Africa, insurance and credit business, shipbuilding and ship repairs, luxury goods, Coca-Cola (from 1965, the first presence of the company in the entire Soviet camp) – and of course a merchant fleet with the Avior and 102 other cargo ships making a total tonnage of more than one million tons. These enterprises were structured into three economic groups: Texim, Imextracom and the Bulgarian Trading Fleet. However, by 1968 politics were beginning to move in a different direction and on March 5, by the Decree number 13 of the Council of Ministers, Texim’s 'Bulgarian cargo fleet' with its sub-units of shipbuilding, dockyards and trade, was incorporated as the Bulgarian Maritime Fleet (BMF).7

A month later the Prague Spring began and although ended that summer, it served as a warning to the Bulgarians. Texim’s flourishing business practices were not to the taste of all and a Sofia Autumn was a high possibility.

To explain what then happened, it’s not too much of a stretch to imagine that in order not to send troops to the Balkans, the head of the KGB Yuri Andropov offered comrade Todor Zhivkov a democratic choice: either you put your friend Naidenov behind bars, or we will replace you with the other comrade Zhivkov. (Todor’s deputy Zhivko Zhivkov). After going through all these options, Todor Zhivkov for some reason chose the first one. On November 10 1969, by Decree number 40 of the Council of Ministers, the hen house was shut and the Texim economical experiment was over. Geto was exonerated of wrongdoing but nevertheless imprisoned for some five years. The cargo ship Avior was reassigned to the Bulgarian Shipping Company (and would remain remained in the Bulgarian fleet until 1980) And the IMO registry records 1970 as the year of renaming.

She became the Hadji Dimitar.

We now return to the encounter between the K-8 and the Hadjii Dimitar. A Wikipedia editor wrote: “After an emergency surfacing most of the crew were rescued with the participation of the Bulgarian ship Avior, later renamed Hadji Dimitar”. While Wikipeida is not always reliable, the messages sent to the Navy headquarters during the K-8 incident explicitly stated that the ship belonged to the Bulgarian Shipping Company. The date of the renaming is listed as that of January 22 1970, which is prior to the encounter with the K-8. Renaming Avior to Hadji Dimitar.

But these are background details. The important thing is neither Yurekchiev, nor Nenkov could possibly make any mistake. They could have called her by the old name Avior, but no, they only referred to the Hadji Dimitar as did the Bulgarian newspaper People's Cause, in that report the Hadji Dimitar is mentioned four times, the Avior not once, nor do these seamen mention any renaming.

In Shigin’s book he thanks some members of the Avior crew, in particular chief officer Georgi Petrov, second engineer Svetoslav Iliev and fourth engineer Vladimir Arkhangelov. The Hadji Dimitar crew for April 1970 had the same chief officer Georgi Petrov, but the second engineer had been replaced by Svetoslav Yurekchiev and the fourth by Vladimir Stoynov. These Hadji crew members did not feature in Shigin’s thanks list.

Summary

Captain Ram Smirnov |

With the closure of Texim and the changes to the Bulgarian cargo fleet, as a result of the struggle for Bulgaria’s health and well-being, the Bulgarians, unwittingly perhaps, caused Andropov to accidentally hand a lemon to his comrades, getting ready to go fishing for the Apollo 13 CM. Clearly the Soviet’s intended the surface component of their plan to operate at one remove, by using a Bulgarian ship for the liaison with the K-8. And they intended that ship to be the Avior, upon which they had placed a Soviet Captain, Ram Smirnov.

But the Bulgarian change of name occurred after the Soviet authorities had made their arrangements for the encounter between the K-8 and a Bulgarian vessel. As if to reinforce what might seem to be speculation, the diplomas for the crew signed by Admiral Gorshkov in thanks for the service to their country and the engraving on the holster of Captain Smirnov’s binocular case all featured the name Avior.

And that’s the reason why, when the Hadjii Dimitar turned up instead of the expected Avior, the K-8 crew had to verify the Captain’s name and check the stern to ensure that the ship was at least out of Varna before committing themselves.

Engraving on the holster of the captain's binoculars:

“To the captain of the Avior cargo, comrade SMIRNOV R.G. from the Commander-in-Chief of the Navy of the USSR 1970.”

So where did the K-8 submarine sink?

Nowhere. She was intentionally drowned. More details are to be found in the book, Autonomous Underwater Robots: Systems and Technologies. Referring to the searching for sunken soviet submarines and in particular K-8 it mentions this fact:

Between 1982-1983 a detailed survey of the area was performed where the submarine K-8 sank in the North Atlantic in 1971 at a depth of over 5,000 metres. The route photographed enabled the creation of a panorama from tens of thousands of photos of the area. The submarine craft made more than 80 deep-sea dives for a total duration of 300 hours.

What’s notable in the book is the fact that the location of the object of interest (the K-8) was known to be within about five miles. Therefore the coordinates were known to an accuracy of up to 5ft (or miles). Where? It was clearly stated to be the North Atlantic. Yet it’s clear that the authors of the book were strictly forbidden from saying where they were searching. The coordinates of whatever was drowned in 1971 are still classified.

But, in addition to the sinking year of 1971, the authors have managed, wittingly or unwittingly, to bypass censorship and give away an approximation of the coordinates, in that they have provided us with the depth of 5,000m. But we do not need accurate ones, although most importantly, they don’t match any official or unofficially announced coordinates! Nevertheless, the authors reported a location where there is no boat.

The boat is probably hidden away in a single cavity, and not even marked on maps. “...At a depth of more than 5,000 m”, states M.D.Agueyev in his book. And photographing the area (tens of thousands pictures) was conducted to verify the safety of the hiding place, or perhaps something else.

Image Autonomous Underwater Robots: Systems and Technologies

by M.D. Agueyev et al., 2005, ISBN: 5-02-033526-6.

If you trust the findings in Autonomous Underwater Robots: Systems and Technology, there is no reason to doubt that:

- The boat sank in 1971.

- Her search was carried out at a depth of 5,000m, the experience demonstrating the effectiveness of the autonomous underwater vehicle when operating at great depths. Everything worked out as it should.

- The search was carried out within coordinates with an accuracy of 5ft (or miles).

Neither the Bay of Biscay, nor Shigin’s coordinates fit the description. What matters is that on the night of April 12, 1970 nothing sank – either in the Bay of Biscay or in an area north of the Azores. And if that was the case, it was indeed a covert operation.8

But in our view, the cargo ship Hadji Dimitar was not heading for the Bay of Biscay.

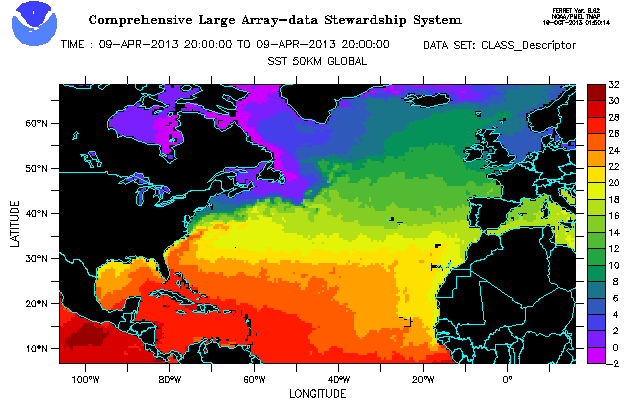

Svetoslav Yurekchiev was a watch engineer, who, among other responsibilities, also oversaw the ship’s seawater cooling system, and he provides another interesting detail: the temperature of the sea was 10°C. There are no such temperatures in the Bay of Biscay, which could just as well place the Hadji Dimitar to the north west of Britain as it could at the Shigin 48ºN latitude’. Satellite sea temperature data can be found here.

Below is a snapshot of the April Ocean temperatures in the North Atlantic:

The Hadji Dimitar was probably going from Hamburg via the north of the UK and on to Cuba. Although timewise, it wouldn’t make much difference if she went through the English Channel. The heavy sea traffic would cancel out any gain. In both cases they would not pass through the Bay of Biscay. So what was sunk in the Bay of Biscay in this case? Was anybody ever there?

Yes, someone was, according to the reports emanating from the Pentagon for publishing in the US media on April 14.

The intelligence-gathering ship was the Agi Laptev and the merchant ship was the Litvy. The actual ships names were: Khariton Laptev and Komsomolets Litvy.

The Americans knew the Khariton Laptev very well. Laptev was indeed an intelligence-gathering ship. But her presence also means the presence of the directly-coded communication with Moscow which means it was a covert operation.

The crew number of 88 is incorrect for a K-8 and the state of the seas and the description of the Soviet ships also varies across reports.

Off the Cape of Finisterre is vague and those earlier reports April 14 from the Pentagon stated that the location of the alleged sinking (it was not confirmed) occurred ‘some 400 miles to the northwest off the coast of Spain’.

More newspaper articles are available here

These newspapers mention neither the Canadian cargo ship Clyvde something (which allegedly warned the Americans about the Soviet sub) nor the Bulgarian cargo ship Avior/Hadji Dimitar. Where were they? In our view they were further north, in the place where water temperature is 10°C and where sometimes it snows (according to Shigin).

But there was definitely a submarine in the Bay of Biscay as well, and at least two ships by her side. She was the second damaged submarine. It was undeniably an extremely unlucky month for the Soviet Navy.

The International Atomic Energy Agency publication Inventory of accidents and losses at sea involving radioactive material, IAEA, Vienna, 2001 ISSN 1011-4289 contains a table – Accidents at sea resulting in actual or potential release to the marine environment:

In the above table of accidents at sea resulting in actual or potential release to the marine environment on page 22 both nuclear submarines appear. One on April 8, 1970, and the second just stated as April. The first is in the Bay of Biscay, the other is just in the north-east Atlantic. No coordinates are given for either vessel. Both have hazardous reactors and nuclear torpedoes – hundreds of 'Hiroshimas'. IAEA doesn’t mention their locations.

8 Apr 1970 Nuclear submarine K-8 (b)

Bay of Biscay – – 4000, 2 reactors

Nuclear warhead(s) No 9.25 PBq, 30 GBq – – –

Apr 1970 Submarine1 Northeast Atlantic – – – Reactor core

4 nuclear weapons

The footnote regarding the first submarine states:

(b) Nuclear submarine K-8 – On 8 April 1970 in Biscay Bay, 300 miles north-west of Spain on board the nuclear submarine K-8, a fire started as a result of oil coming into contact with the air regeneration system. During the fire both nuclear reactors were shut down. As a result of the fire, the rubber seals in the hull failed and seawater began to enter inside the submarine. It sank during a storm on 11 April 1970.

The second submarine: Accident not confirmed.

Here the two nuclear submarine accidents are combined into one with the location shifted from the north to the south and all evidence attributed to one submarine.

James Edward Oberg |

But at the time there were multiple and confusing media reports caused by poor 'media management' (censorship) so somebody should have accounted for all that mess in 1970. And somebody did. Not surprisingly it was NASA controller and NASA propagandist James E. Oberg.

James Oberg is also a scientist, a consultant and a journalist. He knows his Latin, is fluent in Russian, French, and speaks German, Swedish, Spanish, Kazakh and Japanese.

English is not mentioned on the listings, but no doubt he speaks it well. Clearly he is a very intelligent man. You could say a NASA ideologist. (Anyone interested in the saga of the lost Apollo module seems to start off as a space enthusiast, but ends up deeply immersed in the Cold War operations of Soviet submarines.) Within the pages of Uncovering Soviet Disasters (Random House, NY) 1986, in Chapter 5: Submarines, Jim Oberg found that:

Two years later, on April 11, 1970, in the North Atlantic Ocean 350 miles southwest (and upstream) of England, a November-class attack submarine suffered an internal fire and nuclear propulsion system failure. Crewmen were seen on deck trying to rig a tow line to a Soviet merchant ship, but because of worsening sea conditions, the attempts to tow the sub were abandoned. The following morning the submarine was no longer in sight and was presumed lost. The number of crew casualties is not known, but it could have been everyone aboard, as many as eighty-eight. According to a 1986 statement from Captain Guy Liardet, director of British Naval Public Relations, the Russians still “regularly check it [the sinking site] for any radiation leaks.” At almost the same time in 1970 a second disaster involving substantial loss of life apparently occurred, also off the British coast, according to another émigré:

An unidentified nuclear submarine was lost after experiencing a major fire during the Okean-70 maneuvers. Other independent U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) sources corroborate this event. The full text of the heavily-censored CIA interview summary reads: During the exercise, an unidentified Soviet nuclear submarine (class unknown) was tied up alongside an unidentified submarine tender (class unknown) in the vicinity of the Faroe Islands. [Passage deleted.] ... interior of the nuclear submarine caught on fire. The cause of the fire was not disclosed. The fire was fought unsuccessfully, and the submarine captain gave orders for part of the crew to escape to the submarine tender.

The political officer, who had not been ordered to leave the submarine, went on board the tender for fear of his life. The captain ordered the executive officer and several crew members, number unknown, to leave the submarine. 'The executive officer and crew members refused and instead assisted the captain in fighting the fire. The fire could not be controlled and was spreading towards the nuclear reactor. Since there was fear that the nuclear reactor was about to catch fire, the submarine captain ordered the submarine to be scuttled. The petcocks were opened, and the interior of the submarine was flooded to prevent the fire from reaching the nuclear reactor. The number of petcocks opened and the number of compartments flooded was [sic] unknown. The submarine sank "with great loss of life," but the specific number of casualties was not disclosed. It is conceivable that both these accounts are grossly distorted, independent versions of a single event somewhere off the British coast. In light of what we know about distortion factors in émigré reports, that remains possible.”

The first thought that comes to mind is whether to actually believe Jim Oberg. Maybe back in the 1970s the secret services organized a 'leak' of the alleged events on April 14 1970 and in fact there was nothing, and had Jim Oberg just signalled a false 'leak' in 1986?

The answer is straightforward – believe, believe and once more believe, no matter where the boat (or boats) were sinking (or not sinking). It won’t work if we don’t believe this author, even though he possibly made an error by publishing all the above. His mistake can be excused by just one thing: not writing about this event was impossible. Somebody had to account for the mouthy BBC radio announcers chatting on April 14 1970, initiated by a British Defence Ministry spokesman (and the Pentagon in the US media). The best that Jim Oberg could do was to muddy the waters around the events of April 8-14. And we must say he did it well.

It was classic damage limitation.

Jim Oberg’s book is subtitled: Exploring the Limits of Glasnost, “At almost the same time in 1970 a second disaster… in the vicinity of the Faeroe Islands,” was recorded by the IAAE, says Oberg. And that’s it.

The above alone is enough to confirm the covert operation with the submarine K-8, with all the consequences. On the one hand, even if Apollo 13 did actually get into LEO, no matter what, it was still a covert operation.

On the other hand, losing two nuclear submarines in three days is not that easy to accomplish. It's too much. Jim Oberg also understands that. Oberg also understands that, in any case, the information about the fire near the Faeroe Islands (whether it was the same boat, or a different one) gives away a secret operation, and all he can do is to give neither the date nor the location of the second case. And blame ‘uninformed Soviet émigrés for inadequate information. But Jim Oberg cannot imbue emigrants with information as to where aircraft were flying, and their coordinates. Therefore he is silent about these matters. And neither does the IAAE locate the time, nor the place. But the British Navy via the BBC had already stated when and where.

Or maybe they were different boats? In that case it is even worse. Where is the second Hero of the Soviet Union who sunk the second submarine? That year nothing else nuclear powered was decommissioned from the Navy except for K-8. But what if the exercise was on the 14th? And what if, before rescuing K-8, they set fire to the other sub near a mother ship as a training exercise?

Actually, for Veljurov, another point is worth considering. For three days these boat ‘events’ were gradually moving from somewhere north of the Azores to the Faeroe area, then a quite specific course of events emerges where, within an interval of three days, two nuclear subs broke down. And since major war games were going on, then, of course, all NATO air forces were in the air. They collected the information, and of course, they were especially interested in those accidents.

According to Shigin, as the mother ship Volga waited for the approaching 'unfortunate K-8' these events were moving to the area where, as we recall, on April 14 1970 the assistance, sent to help K-8, was near the Faeroe Islands, but they never made it. It would appear that all of the above was a clandestine operation to divert the enemy's attention elsewhere, while 'legitimately' gathering our forces, as already stated, in order to snatch the Apollo 13 CM should it abort. As there had already been a few Apollo CM events prior to April 1970, Soviet Intelligence was fully aware of the splashdown location.

From time to time Bulgarian sailors who participated in this ‘rescue’ operation give interviews to the media or participate in TV programs, but they are extremely reserved when speaking about this incident and don’t like talking about specifics such as the actual date and especially the time of the encounter.9

A quarter of a century after the end of the Cold War, 23 years after the USSR was gone, 13 years since the Kursk was raised by NATO countries, and ten years after Bulgaria itself joined NATO, it is astonishing that the subject of the K-8 is still a taboo issue, at least for Bulgarian sailors. Typically journalists are filling in this data for them. Then from the Russian perspective, thanks to ever increasing quantities of red herrings being supplied by the likes of the Apatit crew, the subject of the lost Apollo CM and the Murmansk handover seems to have taken on a new life.

The question therefore still remains: are these really separate incidents, or two strands of the a same story? It’s for the reader to decide, while bearing in mind that old expression: Caveat Emptor.

Andrei Bulatov and Alexander Boyko

Aulis Online, November 2016

English translation from the Russian by BigPhil

See also The Odyssey of the Lost Apollo CM: Detailed analysis of the April 1970 Event

and Was the Command Module too Light?

About the Authors

Andrei Bulatov graduated from Technical University in the Soviet Union. He first became seriously interested in the veracity of Apollo program after reading the book NASA Mooned America! by Ralph Rene. Prior to that time, Andrei Bulatov had no doubts at all regarding the reality of the Moon landings accomplished by American astronauts many decades ago. Since then he has become deeply involved in studying this subject, and is now engaged in conducting his own investigations, based on various documents published on this topic.

Alexander Boyko gained his Shipbuilding University diploma in the USSR, majoring in electrical engineering. His hobbies are in the arena of military history specializing in the history of the Navy. He became interested in the hoaxed NASA Moon program after being prompted by the strange circumstances of the accident with the Soviet submarine K-8.

Footnotes

-

When recounting the historical events pre December 26 1991, Russia and the Russians are referred to as the USSR and ‘the Soviets’.

-

The official reason for this approach was that JFK, ‘increasingly concerned at the political tension between the two countries sought to use space as means of bringing the USSR to the international community of free nations’. Spaceflight & rocketry: A chronology, David Baker, 1996

-

Dark Moon: Apollo & the Whistle-Blowers, Bennett & Percy, Aulis Publishers, 1999, p.311 and from NASA: ‘When the Apollo Spacecraft passes through the Van Allen belts on its way to the Moon, the astronauts will be exposed to radiation roughly equivalent to that of a dental X-ray.’ p.277 of the Apollo Chronology. https://www.hq.nasa.gov/alsj/CSM29_Apollo_Chronology_pp273-279.pdf (no longer active)

-

http://www.southwind280.com, the ice breaker’s home site has several pages, route maps & pictures worth checking,

-

Boatnerd.com has the data on these ore carriers, and note that although some of these carriers were transferred to Montreal shipping companies and Great Lakes operations, this was after the April 1970 event.

-

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/K-8_(sous-marin) Although detailed, there are still numerous discrepancies with other accounts, not least that on April 8 K-8 was returning from Okean 70!

-

Interestingly, the economic accounts for all of Texim’s operations have different start dates to that of the company start date: Texim accounts date from two years after the 1960 company start, viz 1962-1969 as does Imextracom, while the BMF starts a year before its 1968 start date, viz 1967-1969.

-

In a recent video in Russian media coverage on the K-8 disaster (https://youtu.be/znQnMlnSuNY?t=163 at 2:43) Kashirsky was asked by a reporter to point out the place where K-8 is now on the bottom of the ocean. Using a pen he draws a circle the size of the Bay of Biscay (but outside the Bay although the camera shows the Bay) and the reporter says that the coordinates are still a top secret! Who should know better where it happened?

-

As if to add to the confusion in 2014, the French magazine Sciences et Vie published an interview concerning the K-8. This article also has the ship sinking at 1450 km due west of Brest. Brest is at 48º 25’ 15.62”N, so it’s a fair match for the Shigin latitude coordinate, but the witness, Kashirsky has extended the Shigin longitude of 20º to over 24ºW. He also stated that the home port of the Clyde Ore was Toronto. Why did no one on the boat point out that fact during the witnesses statements already gleaned? This article conveniently confirms the Clyde Ore identity, from a log book ‘borrowed’ by one of the crew who revealed its presence 25 years later, on October 17, 1995 for no apparent reason, to a Moscow newspaper [authors: Vechernyaya Moskva). However, in this log book lies the bearing of the Clyde Ore, it was sighted at TB-250 (true bearing) which means it was coming up on the K-8 from the southwest. Why had no one recorded that in those 16 witness statements? Probably because like Toronto, these details are much later additions to this story. http://www.laboutiquescienceetvie.com/50-idees-recues-sur-la-grande-guerre-1914-2014.html

-

Appendix D references. extract: pp17&18 from Spies to Oligarchs: The Party, the State, the Secret Police & Property transformations in Postcommunist Europe, October 2009, Martin K. Dimitrov Assistant Professor of Government Dartmouth College Hanover, NH 03755 http://www.democracy.uci.edu/files/docs/conferences/dimitrov

Appendix A

DATA on the K-8 627A /November class submarine

Propulsion: two water-cooled reactors VM-A 70 MW each with steam generators, two turbogear assemblies 60-D (35,000 hp total), two turbine-type generators GPM-21 1,400 kW each, two diesel generators DG-400 460 hp each, two auxiliary electric motors PG-116 450 hp each, two shafts.

Speed: surface – /15.2 15.5 knots; submerged –30/28 / knots (project 627 / 627A

Endurance: 50–60 days

Test depth: 300–340 m

Complement: usually 104–105 men (including 30 officers)

Sensors and processing systems: MG-200 "Arktika-M" sonar system for target detection,

"Svet" detection of hydroacoustic signals and underwater sonar communication sonar system, "MG-10" hydrophone station (project 627 submarines had "Mars-16KP"), "Luch" sonar system for detection of underwater obstacles, "Prizma detection radar for surface targets and torpedo control, "Nakat-M" reconnaissance radar.

Armament: 8 533 mm bow torpedo tubes (20 torpedoes SET-65 or 53-65K). [Wikipedia]

Appendix B – The First Encounter

-

That day we saw a ship on the horizon. The commander ordered us to fire several flares. The ship changed its course and headed in our direction. When she came closer, we saw a large maple leaf on the funnel and the inscription "Montreal" on the side. She was a Canadian cargo ship. At a distance of 100-150 meters she went around our boat and returned to the previous course

How so? Why didn’t the Canadians help you?

We didn’t ask for help. Having seen that it’s the 'capitalists', not to mention a NATO country, our commander decided not to contact them. I saw that Canadians on the bridge were staring at our boat. Apparently, they were trying to figure out what the matter was. But since we didn’t give any signs for help, they left. Ostensibly, the Canadians reported us, and soon an American four-engine airplane appeared above our boat. https://zn.ua/SOCIETY/prodolzhat_borbu_za_zhivuchest_lodku_ne_ostavlyat.html

-

Similar account. Time 14h 15m. 5 red flares. "Montreal" on the side. Difference: Canadian captain might have been scared of machine gunners(!) on our deck. Soon American spy planes "Orion" appeared and began dropping sonar buoys. However, even if the Canadian vessel had decided to help us, this still would not have happened. At the time, seeking assistance of a foreign ship shall be considered a crime. http://www.gorod.cn.ua/ru/news_25446.html

-

Some ship appeared on the horizon. When she came closer we understood it wasn't our ship. We took out machine guns. The Canadian intelligence ship walked around us and disappeared. http://fakty.ua/55033-quot-ya-i-teper-muchayus-chto-ne-otkryl-dver-drugu-zadyhavshemusya-v-goryacshem-otseke-ne-uspokaivaet-dazhe-mysl-o-tom-chto-esli-by-sdelal-eto-vmeste-s-nim-mog-pogibnut-i-ves-ekipazh-podlodki-quot

-

Time: 14h 15m. A ship appeared on the horizon. 5 red flares. She was a Canadian cargo ship Clyvde Ore. The vessel approached at the distance of 15 cables (1 cable = 185 m) and turned back on course. http://submarine.sten.lv/cp/z86.shtml

Time 14h 15m. 5 red flares. It soon became clear that she was a cargo ship. Funnel marking defined nationality — Canada. Name of the ship was Glow de Or. Now here is a difference. Commander Bessonov and his security officer decided to accept help from a ship of NATO country. But something unexpected had happened: The Canadian ship came to the distance of 15 cables and turned away!

-

Time: 14h 15m. 5 red flares. Canadian Clyv de ore. Soviet crew tried to contact Canadian crew on the bridge (signal “L” – ask to stop the ship, I have an important message) but the Canadians turned away. NATO planes soon appeared and started taking pictures of the helpless vessel. https://military.wikireading.ru/2956

-

Foreign cargo ship not far away. The boat signaled SOS — 5 red flares. The vessel circled around and left. http://vpk-news.ru/articles/342

-

Our main radio transmitters broke down and UHF-station was good only for plain sight distance. The sailors could use only signal flares. Time 14h 15m. A cargo ship. 5 red flares. Canadian Glow de Or. Distance 15 cables. She changed the course and left. We still don’t know why they did so. Even cold war shouldn’t have canceled either the brotherhood of the sea or the Warsaw Pact. http://www.russian.kiev.ua/material.php?id=11604829

-

It seemed that luck turned, when at 14 hours and 15 minutes on April 9, the Canadian cargo Glow de Or saw our signal lights, but the joy was premature: once she approached the Canadians simply turned around and left K-8 to its own destiny! But why? It is still unknown. http://morpolit.milportal.ru/nataliya-vasyuk-gazeta-novaya-kisloroda-bolshe-net-rebyata-proshhajte/

-

Time: 14h 15m. 5 red flares. Canadian Clyvde Ore. Distance 15 cables. She left. http://www.simvolika.org/mars_105.htm

-

Similar to previous accounts. http://www.vu.mil.gov.ua/index.php?part=article&id=936 (link no longer active)

-

Different account. Canadian cargo ship apparently saw smoke on the Soviet boat. Distance 50 cables. Commander Bessonov refused help and hoisted signal “I have a dangerous cargo, don’t need help, leave us alone”. One red flare, loudspeaker, a flashing beacon on the sail. Canadians — being good sailors — gave our coordinates in the air, thanks them for this. http://chtoby-pomnili.livejournal.com/140266.html

-

5 red flares. Probably Canadian cargo. Apparently got scared of radiation and left. http://adsl.kirov.ru/projects/articles/2010/04/21/predtecha/

-

Canadian cargo ship Clyv de ore. She didn’t respond to our signal for help. http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/599326

-

Time: 14h 15m. Our boat gave SOS signal — 5 red flares. Canadian cargo Clyv de ore circled the boat at 15 cables and left.

-

Similar to previous. http://galea-galley.livejournal.com/17675.html

Appendix C – The Second Encounter

-

In the morning of April 10 on the horizon we saw lights of a ship. Although there were fears that it was once again a ‘capitalist’, the commander ordered us to fire signal flares. This time we were lucky: the boat was approached by a Bulgarian transport the Avior. You can imagine how happy we were: "Ours, Slavs!" They were going from Cuba to England, carrying sugar. The vessel came very close to the submarine and through the loudspeaker we could carry on a conversation with his captain. And here is another piece of luck: on Avior there was a Soviet captain-coach.

https://zn.ua/SOCIETY/prodolzhat_borbu_za_zhivuchest_lodku_ne_ostavlyat.html

-

Another vessel. Again we fired flares. Bulgarian cargo ship Avior. Immediately through Varna we sent a cable to Moscow. Now K-8 could count on help. http://www.gorod.cn.ua/ru/news_25446.html

-

In the morning the lights appeared again. We fired red flares: “Do not come close!” The ship was gone. Then she reappeared. It was a Bulgarian cargo ship Avior, which was going from Hamburg to Cuba. "What kind of assistance do you need?" asked the captain. "Send a code for Moscow”. But they did not have such a frequency and they sent it to Varna instead.

-

Only after 30 hours was the boat accidentally discovered by a Bulgarian ship Avior. Not to pull hard on the boat, the cargo ship moved aside and began to heave to. Her radio station sent a message to Varna about the incident. http://submarine.sten.lv/cp/z86.shtml

-

On the horizon above the stern we saw the outline of a ship. As she approached, we saw a superstructure and a funnel, but no markings of her nationality. The funnel was not white, but cream with a red stripe and without a hammer and a sickle. Involuntarily the question arises: whose vessel is this? Then we saw the name Avior and only when she caught up with us, using a trumpet (made from tin cans of crackers) we made connect with the bridge. As it turned out she was a Bulgarian cargo ship, and the captain-coach was our compatriot. The ship was moving forward on inertia and then at the aft we saw the home port of Varna.

Our radio did not work, and only thanks to this cargo ship, in the second half of the day we were able to send a message to Moscow about the accident through the Bulgarian port of Varna.

The dawn was joyless: fire, storm, lack of communication and complete uncertainty ahead.

— Navigation lights! I see navigation lights! – Suddenly shouted the signalman.

People on the bridge came to life.

— Where? Where?

— Right fifteen! Yes, there it is, clearly seen! – the 1st Class sergeant Chekmaryov was pointing with his hand.

Shielding their eyes from the wind, the officers began to stare in that direction. Exactly! The red side light and the two white ones on the masts were clearly visible.

— It looks like a cargo ship! – looking through binoculars, suggested the 2nd rank captain Tkachev.

— Fire flares! – Ordered the CO.

One after another five red flares were fired into the sky.

— She is turning on us! – a few voices shouted at once.

It was getting lighter. On the bridge Kashirsky, Bessonov and Anisov were quickly encrypting a radio message. When the vessel approached a little, the boat gave the signal "Izhe Vedi”, which in the International Code means "I want to establish a communication." Then we sent two more letters "Ljudi" and "Myslete" – "Please stop the engine, there is an important message" and "Our engine has broken down.” The ship signaled that everything was understood.

Now it was clearly evident that the ship, which approached the nuclear-powered vessel, was a dry cargo ship. On the yellow funnel a wide red stripe stood out clearly.

— I think it’s ours! – rejoiced the K-8 bridge.

— Identify your nationality! – Kashirsky shouted through the trumpet made from a rolled tin can of biscuits.

In response, they waved something, but the words were lost on the wind.

— Are you Russians?

— Russians! Russians! – they happily shouted from the ship. The boat immediately perked up.

The dry cargo ship turned slightly and the name Avior was clearly seen on her stern and the home port Varna.

— Doesn’t matter. They are ours, brothers! – the submariners were talking to each other. Now it will go smoothly.

Meanwhile, the nuclear submarine commanders were figuring out the possibility of transmitting a radio message. On Avior they sighed:

— We don’t have your frequency. Our transmitter is discrete!

— What do we do? – Kashirsky looked around at the officers standing next to him. Only one thing left, to give the message through Varna!

The commanding officer, deputy political commissar and osobist (KGB type) nodded affirmatively. Once again, armed with a trumpet the division deputy (Kashirsky) dictated a coded radio message to the Bulgarian ship – a jumble set of digits to transfer to Moscow.

From Avior was shouted:

— I am staying near you until I get confirmation from Varna!

— Give our location and the forecast! – was requested from the boat.

— Latitude 48°10' North. Longitude 20°06' West – immediately responded from the vessel.

— The weather forecast is bad. A cyclone Flora is coming from west of the Azores, and in our area the expected magnitude is 6-7 by the evening. What do you need? [Flora was in 1963! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_historic_tropical_cyclone_names] [Awesome catch!]

http://avtonomka.org -

Only in the morning of April 10 did lights reappear on the horizon. Again red flares. Soon a Bulgarian transport Avior came to K-8 and hove to. The captain of this vessel was a countryman from Murmansk Ram Germanovich Smirnov. Bulgarians lowered two boats and transported onboard 43 submariners. Via a tricky process they transferred the coded cable to Moscow through the Commander of the Navy of Bulgaria. https://military.wikireading.ru/2956

-

Only on April 10, following almost two days of desperate struggle for survival of the boat and crew, did the Bulgarian ship Avior came to the submarine. The captain of the ship, who turned out to be a compatriot, asked via trumpet what was wrong and what the crew needed. The K- 8 commander asked if it was possible to contact Moscow. From the ship they replied "Only through Varna." After the ship transmitted a cable the submarine thanked and allowed them to leave. However, the captain decided to stay close to the wounded boat and wait for response from his superiors.

http://vpk-news.ru/articles/342 -

It was the morning of April 10, when another vessel showed up on the horizon. After five more flares a Bulgarian cargo ship Avior approached the boat. The captain Ram Germanovich Smirnov was from the Murmansk Shipping Company. How happy these Soviet sailors were when they heard from the cargo ship: "Hold on brothers!" By a complex chain of radio relaying (Bulgarian Shipping Company in Varna – Bulgaria's Navy, also in Varna – Duty Officer of the Black Sea Navy in Sevastopol – the Navy Main Staff in Moscow), and although not immediately, it was briefed on the situation. And Soviet cargo ships as well as Navy ships rushed to rescue the defenseless K- 8. http://www.russian.kiev.ua/material.php?id=11604829

-

Only on April 10 did the Navy Main Staff find out that a Soviet nuclear submarine was sinking in the Atlantic Ocean. And all thanks to the Bulgarian cargo ship Avior, which arrived on the scene, after having seen flashing lights. K- 8 was already being flooded, when the order from Moscow to assist was given to all nearby vessels. http://morpolit.milportal.ru/nataliya-vasyuk-gazeta-novaya-kisloroda-bolshe-net-rebyata-proshhajte/

-

On April 10, 1970, just 30 hours after the incident, K-8 was accidentally discovered by a Bulgarian ship Avior with a Soviet captain-coach on board. Her radio station sent a message via Varna about the accident. http://www.simvolika.org/mars_105.htm

-

Nothing new, same info. http://www.vu.mil.gov.ua/index.php?part=article&id=936 (no longer available)

-

Canadians (honour and glory to them), being real sailors, gave the coordinates of the sinking boat. On hearing this, the boat was approached by a Bulgarian transport Avior. At that moment, the radio communication cabin had already burned down. Through Avior a connection was established with Moscow via the Russian embassy in Sofia.

-

Nothing new, same info. http://adsl.kirov.ru/projects/articles/2010/04/21/predtecha/

-

Nothing new, same info. http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/599326

-