Apollo-Soyuz: The Joint Hoax?

Chapter 11

Filming in a reduced-gravity aircraft

In the previous chapter we discussed NASA’s Apollo-Soyuz Test Project documentary.1 We will now examine some points of interest from a program originally broadcast on Soviet TV in 1975.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the domestic ASTP documentary, May 23, 2014, based on the 1975 television archives

Following the publication of the article that formed the basis of this book, the author received an interesting letter from a reader named Dmitry Goryunov who lives in the city of Kemerovo, Russia:

After reading the article Mission Soyuz-Apollo – the Last link in the Moon Hoax? I want to draw your attention to a few strange facts related to the video Soyuz-Apollo, Handshake in Space 1975, (screened on May 23, 2014) since posted on YouTube. In the video there is a sequence of the group lasting 9 minutes 03 seconds, from 15:26 to 24:29.

The first episode: at 17:17, all three participants synchronously move to the right, as if they were in a car that runs over a bump.

The second episode: at 22:54 next to Kubasov a small bright object spontaneously starts flying in circles, but at 23:00 it is static until the picture "explodes" with a series of busy actions. Kubasov "hangs" the camera, while releasing the "folio", which he holds in his hands. And the "folio" instantly unfolds into a "book", which we do not observe at all. And at 18:03, when he holds half of the "folio" with his hand, the other half just hangs down.

Stafford takes his headset off his head and leaves it, Leonov does the same, but it doesn't look so convincing, and at 23:45 (after 45 seconds) all the activity ends, nothing flies around, everything is removed from the frame or held in the participant’s hands, and the scene returns to being static again.

A similar episode runs from 25:46 to 26:11 [lasts for 25 seconds], the same fussing around; they take off/put on their headsets, objects fly about in the frame. It seems that the activity occurs precisely at those moments when weightlessness begins.

The strangest episode: is from 10:39 to 12:44, it looks like a live broadcast on the display screen in the MCC [Mission Control Center]. At 11:58 the picture changes, it first shows an American astronaut from behind, he glides half way into the compartment with two cosmonauts and one astronaut, and then the camera in the compartment shows all three but does not show the astronaut who had just flown into the compartment.

It seems that instead of watching a live broadcast, the controllers in the American MCC are viewing previously recorded and edited footage – resulting in a broken sequence of events. And when four people are filmed from two different angles, does it assume the presence of six people? I would like to hear your opinion! – Dmitry Goryunov, July 30, 2015.

The author suggests watching the above video. Ideally, the episodes indicated by D. Goryunov should be viewed at least three times because many events occur, they are quite brief, and the viewer cannot immediately discern all the questionable moments (which of course exactly what the hoaxers count on).

Below are several freeze frames from the film under discussion, but the author emphasizes that still pictures cannot substitute viewing of the film itself. They can only draw attention to the most interesting moments of the film.

The sequences can be viewed in slow motion mode on YouTube – just click the gear at the bottom right and select playback speed 0.25 ... 0.5. Or download the movie and view it on a player with slow-motion.

In Chapter 4 the author stated that NASA deliberately prearranged for the television reports to be transmitted from orbit with very poor quality. Therefore (if you decide to view it) readers will have to accept both the low quality of the video and the resultant poor quality of the still pictures reproduced below in Figure 3. Repeated viewings of these episodes are recommended.

What is a zero-G or reduced-gravity aircraft?

Film-making in those days could draw on a selection of special techniques to simulate weightlessness. But as a rule these techniques focused on one subject. Most often it was a person or an object floating around in apparent reduced gravity. But what if you wanted to demonstrate the weightlessness of several subjects at the same time? – say Kubasov's camera and his "folio", or the headsets of Leonov and Stafford?

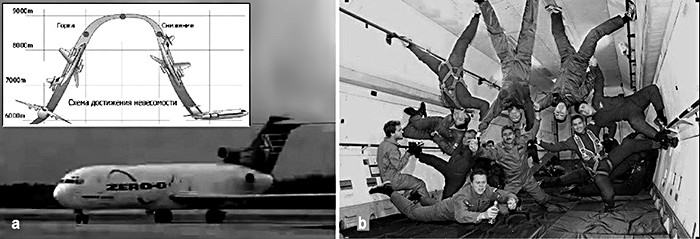

For those in 1974 who were responsible for the production of the television reports of the "handshake in orbit" for the 1975 event (Chapter 4), filming in a reduced-gravity aircraft would be the answer. On board such an aircraft one can create, albeit for a short duration, a state close to reduced gravity (or quasi-weightlessness)1. Such aircraft were available from the very beginning of the space era and deployed for training future cosmonauts and astronauts. Usually large transport airplanes were (and are) converted into reduced gravity craft. It is possible to place an entire space vehicle (or even two) inside such an aircraft (Figure 2). Today anyone can take a ride in one for a reasonable price.

Figure 2a flight path and b, Inside a reduced-g aircraft, also known as the zero-G, or 'Vomit Comet' 2

'Reduced gravity’ is the colloquial term for the condition of quasi-reduced-g which is created within airplanes by flying a special trajectory in order to achieve such a state of quasi-weightlessness onboard.

To achieve this, specially trained pilots transfer the aircraft to almost free fall at certain sections of the flight. They do this by following a parabolic flight path relative to the center of the Earth which will provide the aircraft’s occupants with the sensation of weightlessness for a brief period of time (from "22-28 seconds depending on the conditions of the flight"2). Then there is a subsequent descent and transition to ‘normal’ horizontal flight conditions. (Figure 2a).

Just before the start of the of quasi-reduced-g period a warning light is illuminated over the flight deck. And during this short period, the pilot must very subtly control the engines’ thrust, because air resistance slows down the aircraft, and this resistance needs to be accurately compensated.

Cosmonauts and astronauts on board a reduced-gravity aircraft and the behavior of V. Kubasov’s movie camera

Understanding the basics of a reduced-gravity flight will help us understand the various oddities to which D. Goryunov (D.G.) drew our attention:

1) D.G.: all three participants synchronously move to the right, as if they were in a car that runs over a bump.

There are of course no bumps in orbit, but sometimes there are during an aircraft’s flight. These are caused by air pockets. An aircraft can also swing to one side even without an air pocket if a pilot were to abruptly correct the aircraft’s course.

2) D.G.: at 22:54 next to Kubasov a small bright object spontaneously starts flying in circles.

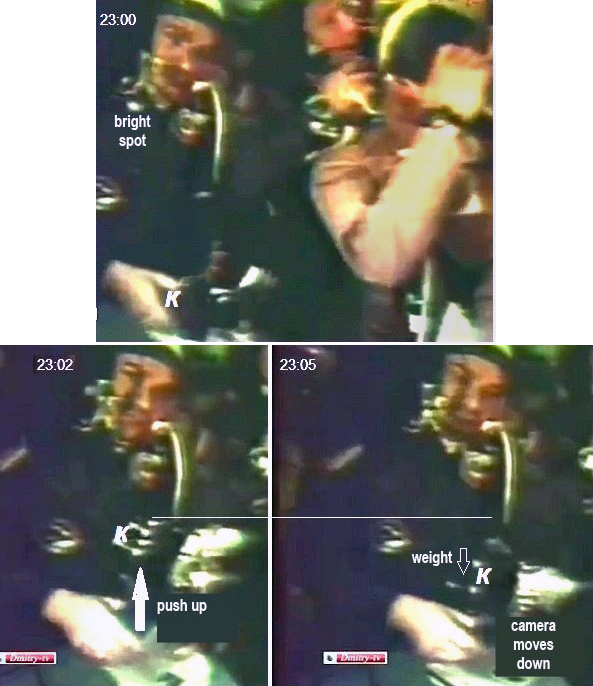

Indeed, on the screen against Kubasov's face, a bright spot is moving in circles, then along a more complex trajectory (see caption Figure 3, at 23:00). Kubasov does not react in any way to this spot. In fact, he doesn't see it, because no real "bright object" is spinning around Kubasov. But we can see a light flare, swirling against Kubasov's face.

It can be assumed that at 22:54 a light signal is switched on in the cabin of the aircraft, warning that in a few seconds the pilot will be transfering the aircraft into quasi-reduced-g flight mode. Sometimes an illuminated ball hanging on a wire is used as an additional warning sign. Somehow a reflection from the ball hits the front element of the camera lens or the glass filter while shooting the scene.

If the ball is swinging slightly, then it may well produce a flare, rotating in a circle. The movement of the ball suddenly decreases during the period of quasi-weightlessness. And then the light flare from the ball freezes or disappears altogether – that’s what we see at 23:00.

During the onset of quasi-reduced-g the cosmonauts and astronauts are determined to show its effects to the viewers and thereby convince us that they are in orbit. In particular, V. Kubasov is trying to do this with the help of his movie camera, which he previously held in his hands. But he did not take into account the fact that the state of quasi-weightlessness does not completely neutralize an object’s weight.

Figure 3. V. Kubasov tries to demonstrate weightlessness with the aid of his movie camera (screenshots from the video). A bright flare, which for a few seconds spins in front of V.Kubasov's face, disappears immediately after 23:00

3) D.G.: at 23:00 it is static until the picture "explodes" with a series of busy actions.

Yes, six seconds after the light signal illuminates the state of quasi-reduced-g commences. At the time (23:00) Kubasov is holding the camera which he plans to allow to just hang in the air. Stafford wants to demonstrate the same with the help of his headset. Therefore Stafford brings his hand close to his head, getting ready to take off the headset as soon as the quasi-weightlessness commences. Just this synchronous readiness of Kubasov and Stafford shows that the quasi-reduced-g they are waiting for will be short-lived (Leonov is in the background and his manipulations are hardly distinguishable).

4) D.G.: Kubasov “hangs” the camera.

Here D. Goryunov is a slightly incorrect. Kubasov does not hang it but he attempts to hang the camera. As soon as he releases it, the camera immediately drifts down. We will observe the camera's behavior in several frames from the video.

At 23:02 Kubasov, with a slight finger movement from below, pushes the camera upwards. It does not resist, but after it barely moves up, it starts slowly moving down again (23:05).

Then Kubasov takes the camera with his hand and leaves it high enough (Figure 4, 23:07). But, as soon as he releases his grip, the camera floats down again. This is at 23:12. Stafford at the same time takes off his hat, but the camera fails to follow it. And relentless Kubasov at 23:17 again pushes the camera up. It rises a little, then decisively descends to the cosmonaut’s knees (23:31). From this moment on, V. Kubasov no longer tries to repeat his trick.

All of this suggests that these three people are not in orbit at all, but are just simulating being in low-Earth orbit.

Figure 4. V. Kubasov repeats his attempts to demonstrate weightlessness with help of a movie camera, but in vain

Should the reader wish to compare a state of quasi-weightlessness with real weightlessness in low-Earth orbit, see the video from the series Life on the ISS.3

5) D.G.: at 23:45 (after 45 seconds) all the activity ends.

These 45 seconds include both the trickery and a weakness in the fakery. The episode lasts 45 seconds, although, as described above, on reduced-g aircraft the best quasi-reduced-g lasts "22-28 seconds depending on the conditions of the flight"2. Prolonging the state of quasi-reduced-g by 1.5 times is possible only if the pilot receives an order to deviate from the optimal trajectory of the aircraft's descent.

However, in accordance with the laws of physics, the quality of this quasi-weightlessness deteriorates. That's why Kubasov's movie camera doesn't hang in the air.

6) D.G.: It seems that the activity occurs precisely at those moments when weightlessness begins.

This is a totally correct observation.

D.G.: It seems that instead of watching a live broadcast, the controllers in the American MCC are viewing previously recorded and edited footage.

This is also correct.

Conclusion

The findings in this chapter suggest that the cosmonauts and astronauts were filmed in advance of the mission on board a reduced-gravity aircraft. The footage was probably shot the very same year, in 1974, when all the transmissions "from orbit" were being prepared (Chapter 4).

ISBN: 978-1-898541-19-6

Aulis Publishers, January, 2019

English translation from the Russian by BigPhil

References:

Internet links verified January 18, 2018

1. NASA video clip (9:41). Apollo-Soyuz Test Project Documentary Pt 2 of 3. Posted 08/04/2009 on the StaffordMuseum YouTube channel, NASA link to this video copied 07/22/2016

2. http://www.starcity-tours.ru/category/zvezdny/reducedgravity (rus), http://www.gozerog.com (eng)

3. Video with real states of weightlessness:

- ISS: orbital home – Time 3:10, 4:48, 5:58, 8:20

- Soyuz TMA-20 History of flight – Time 7:10

- Space, Moscow – Time (Salyut 6) from the second minute

This chapter is licensed under

a Creative Commons License