Apollo-Soyuz: The Joint Hoax?

Chapter 9

Docking "on invisible sky rails"

Space docking and how it looks in reality

Each spacecraft has a reaction control system that uses thrusters to provide attitude control, and is capable of providing small amounts thrust in any desired direction or combination of directions. Located around the sides of a craft, these attitude control thrusters are used to adjust the craft's position when in space. As and when necessary, the system fires brief thrusts of propellant to the right or left of the craft, and even in both directions almost simultaneously. An attitude control thruster firing in action can be seen in Figure 1, photographed through a window of the International Space Station (ISS).

Figure 1. The cargo spacecraft ATV of the European Space Agency docking with the ISS. The exhaust of an attitude control thruster firing is clearly visible to the left of the craft1 image: ESA/NASA (Note the stars)

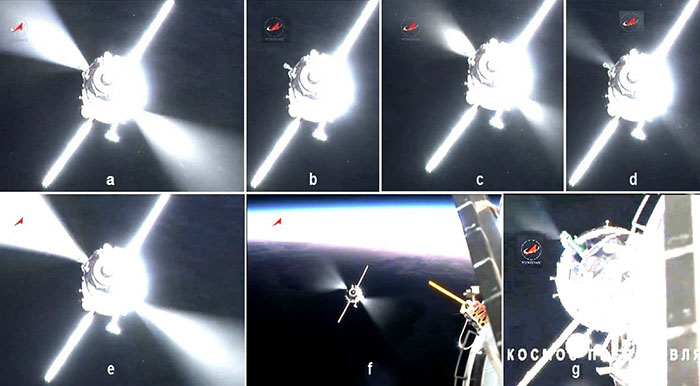

In the video Flight in Space produced by the Roscosmos TV studio,2 the operation of attitude control thrusters is shown in the dynamics of the rendezvous and docking manoeuvres of the Soyuz with the ISS:

Figure 1a. Flight in Space video

Figure 2 has screenshots from this video production. Abrupt flashes of propellant from the attitude control thrusters (at around 2 mins 20 secs) are visible from time to time against the background of the cosmos (sometimes firing several times per second). The last pulse flashes very close to the docking target (at around 2 mins 49 secs and Figure 2g). This action is absolutely necessary as docking elements of both the craft and the space station must align accurately. Consequently, an actual docking with another object in space is accompanied by the spectacle of numerous and frequent flares from the attitude control thrusters firing from the approaching craft.

Figure 2. Flashes from the Soyuz attitude control thrusters during its approach and docking with the ISS

Evidence from 1975

A well known Soviet space writer and serious Apollo propagandist, Y. Golovanov, was in attendance at NASA's Mission Control Center (MCC) in Houston on July 17, 1975. He wrote:3

I will remember the moment of docking for the rest of my life. The television image was being projected onto a large screen in the Houston Mission Control Center.

Initially the Soyuz hovered over the very edge of a bright halo of the earth's atmosphere, then it began to grow rapidly on the screen. The Soyuz was precisely aligned. The Apollo, whose gateway module was in the field of view of the external camera, was approaching very confidently. It was not at all noticeable that Apollo was aiming. On the contrary, the impression was that Apollo was rolling towards the Soyuz on invisible sky rails. The guides of the docking assemblies immediately entered each other smoothly, firmly and almost silently. There was an outburst of applause. (emphasis added)

NASA video on Apollo and Soyuz docking

And now let's consider part 2 of the NASA documentary of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project4 covering the same docking that Golovanov observed on the big screen in the Houston MCC. The duration of the video is 9 mins 40 secs, of which only about 40 seconds cover the actual docking. The video was posted on the Internet 34 years after the event in 2009, by the YouTube user StaffordMuseum:

Figure 3. NASA Apollo-Soyuz Test Project Documentary video Pt 2 of 34

Figure 4 has screenshots from this production. At around 3 mins 05 secs the film intercuts between the Soyuz and the Apollo craft. Figure 4a is the initial frame of the entire docking episode in the video,4 Figure 4f is the last one.

Figure 4. Sequence of screenshots of the Apollo and Soyuz docking from the NASA video. In Figure 4c, the white arrows indicate locations of the Apollo attitude control thrusters4

Y. Golovanov was not entirely accurate when he stated that from the very beginning "The Soyuz was precisely aligned". In Figure 4a it is clear that initially the axes of the spacecraft are significantly misaligned with each other. In such a case as this, throughout a real docking, the attitude control thrusters of at least one of the craft (and, perhaps, both) must operate to correct and adjust the alignment of the two craft.

In the Figures 4b-f both objects are already clearly distinguishable and visible against a helpful black background. However, there is not a single flash from any of the attitude control thrusters. According to the official ASTP program, Apollo was to be the active craft during the entire docking process. That means the craft’s thrusters would have needed to fire frequently. In Figure 4c the added white arrows show the location of the thruster nozzles on the Apollo. But watching this video you won’t see a single flash – either from the active Apollo craft or from the passive Soyuz.

Therefore the big question is whether or not these are real spacecraft manoeuvring in space?

It is more likely that the video4 shows docking of two mock-up craft, made in a well-equipped, specialist film studio. Naturally, for a sequence that portrays the docking of models, no attitude thrusters have to fire nor are they even required. And precise alignment of the models isn't needed either. The docking sequence takes place using mechanical control. In such a scenario in the words of Y. Golovanov, it will run "on (sky) rails". In the opinion of the author, it is far more likely that the docking sequence of these models was performed in the studio with the aid of cables or even virtually invisible monofilament wires. (Similar to those used for the wire flying of astronauts.)

The author of the book 100 Stories About Docking, professor, and corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences V.S. Syromyatnikov described how initially Soyuz docking units were tested on Earth with the aid of cables:5

1.8. In preparation for the first docking of the Soyuz spacecraft, it was decided to build full-scale mock-ups of the craft and suspend them so that they would float in the air. We were satisfied with the imitation of space motion on such a test bench.

A single glance at the pictures in Figure 4 is enough to understand that during the filming of this episode, high quality and detailed models of Soyuz 19 and Apollo were used. Such models do exist and have been in a US museum since that same year, 1975 – such as the full scale model of the Apollo-Soyuz that is on display at the Smithsonian, in Washington, DC. It is entirely possible that scaled down copies of these mock-ups were used to shoot the docking procedure.4

Figure 5. Apollo and Soyuz 19 models now on display in the Smithsonian, Washington, DC

The bottom line is that throughout the entire event we have not seen a typical space docking of these two craft. No flashes whatsoever, combined with a total absence of any exhaust from the thrusters strongly indicates that the two spacecraft were not actually docking in space at all, but they were simply models or mock-ups filmed on Earth.

ISBN: 978-1-898541-19-6

Aulis Publishers, September, 2018

English translation from the Russian by BigPhil

References

Internet links verified January 17, 2018

- Photograph by ESA astronaut André Kuipers during his PromISSe mission, 2012

- Flight in Space, a production by the Roscosmos TV studio

- Y. Golovanov, The Truth About the Apollo Program, EXMO Press, 2000, ISBN 9785815301061 (Rus.) For the text on the docking, see Chapter X, Afterword, Handshake in Orbit

- NASA video clip (9:40). Apollo-Soyuz Test Project Documentary Pt 2 of 3. Posted on 08/04/2009 on the YouTube channel by StaffordMuseum, NASA link to this video copied 07/22/2016

- V.S. Syromyatnikov, 100 Stories About Docking, M. Logos, 2003, Section 2.17, Mission

https://royallib.com/book/siromyatnikov_vladimir/100_rasskazov_o_stikovke.ht

This chapter is licensed under

a Creative Commons License